Retrospection is the foundation for any highly effective organization. It’s the engine for a thriving Growth Mindset.

There are different scopes to retros from the sprintly team retros, to postmortems about big projects or launches or failures, to the accumulated learning as teams constantly iterate and experiment within their scope (e.g. “How do we get customers to try new features, or share content, or download the mobile app or whatever?”)

In my experience, the right process depends on the scope of the thing you are retrospecting.

Three questions

I think software engineers are generally familiar with the standard retro process. Basically, get the main players in a room and list

- What went well?

- What went poorly?

- What to do differently?

This “default” retro style is great for a relatively contained scopes. For example, “The technical quality and rollout of a launch” might be scoped to features vs quality tradeoffs, the level of monitoring and telemetry, the coordination when switching on/off feature gates and whatnot. Other contained scopes might be “marketing” or “design”.

Sometimes the three columns are “start”, “stop”, “continue”.

Either way, they are most effective when crisp action items are created and tracked.

The Journalistic Retro

The second process works well for much larger and ambiguous scopes. That might be “Retro on the massive October company launch” or “Retro on the failure of a 5 year technical project.” For those, I’ve found an effective process has a more “journalistic” approach.

You start by finding someone (the right person) to interview everyone from a somewhat outside journalist perspective.

“Look, I’m just interested in talking to you about the facts and your observations and perspectives. You can be 100% candid because I’ll manage it well.”

That person needs to be trusted so people really open up to them, yet separated enough that they won’t inject their own biases (as much as possible).

Just after joining a new company, I volunteered to retro a recently failed project. People found it striking and credible when my retro just bluntly stated “This person wanted to go left. That person wanted to go right. The escalation point was the VP of Engineering that made this decision. That led to a technical approach with all this friction and contention.” Everyone was like “Yep!” and “Hell yes.” For a recent Big Launch retro we had a senior leader in the design org interview people. I don’t know exactly how many interviews she conducted but it might have been 30+? Product Managers, Sales, Marketing, Design, VPs, TPMs, platform engineers, product engineers, the CEO. That first writeup doesn’t need to win a Pulitzer. In fact, the first writeup was rough and just bullet points in a lot of places.

The second step is for that person to develop a set of root causes. There’s needs to be a lot of judgment here, and they’ll want to share and iterate with leadership as they do this. I’ve found it effective to have that person own the final recommendations versus having some “consensus” approach that tends to sugar coat or downplay embarrassing problems. Those recommendations are stamped by the higher level of authority, and shared with the right messaging to the right people.

For example, a core judgement might be, “Different parties believed we were heading for failure, but no one felt the agency to stop the train… in fact, given the structure of things, no one person might have been able to… it’s totally broken leadership.” The message to senior leaders should be articulated just like that. The message to the whole company will need thoughtful articulation, but should not hide the problems. Some judgements should simple be shared verbatim.

Finally {

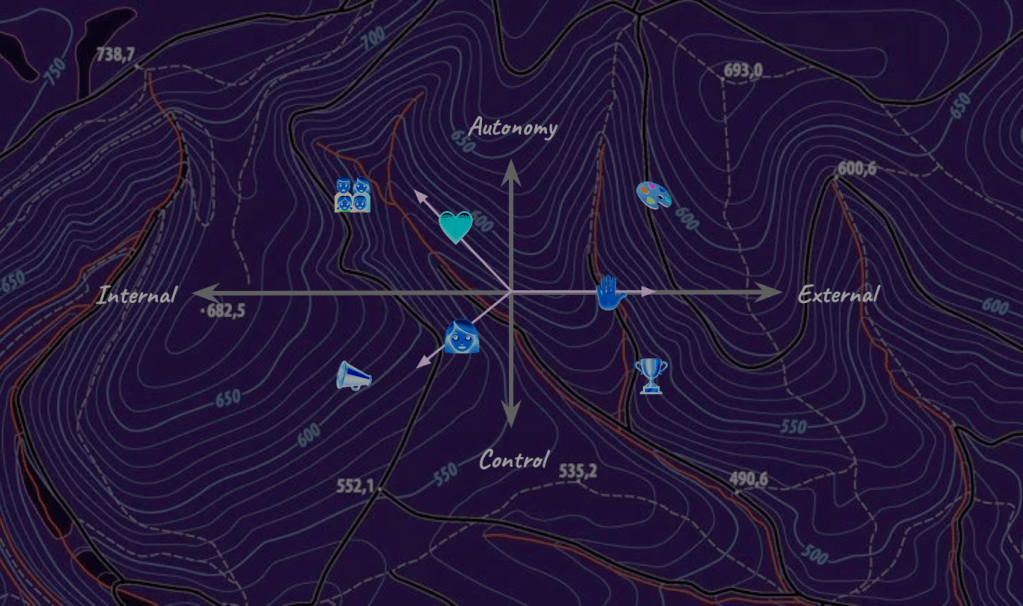

It is critical that retros of larger projects and smaller experiments to be available and discoverable. It obviously allows those learnings to be widely shared and understood at the time, but I’ve also found them useful as something to revisit much later.

In my experience, it’s easier to be skeptical than optimistic, and ideas can often be met with, “Yeah. We tried that. Doesn’t work.” When that happens, we can now go dig up those retros and see if that’s really true. Was it really tried before? Was it tried well? We the reasons “it didn’t work” apply to this new idea? Is there just a better way?

Leave a comment