It doesn’t take long in tech to understand that different companies operate with very different cultures. Within large companies, the culture often varies from organization to organization and team to team, but I’d bet the description of the top-level culture at places like Amazon, Meta, Google, and others would sound relatively consistent from person to person.

As a leader, it’s important to understand company culture, whether to adopt it or adapt to it better.

If you dig around for frameworks on company cultures, you’ll find a lot. People, particularly consultants, have developed various ways to analyze (and inflect) culture. I suppose this isn’t surprising since “culture” is both complex and vague. Different ways to dissect may be more effective based on needs. Are you trying to create more cohesion between very different functions within a company? Are you looking to drive strong alignment between top leadership and the teams on the ground? Are you driving a deep transformation?

However, at the highest level, I have found some simple ways to frame or categorize corporate cultures. I’ll share a few here that you can use in conversations with others about the culture you have or want.

First, let’s start with a tweet from Andrew Chen. It stuck with me.

Head/Heart/Hands is often used to describe attributes of personal leadership, so it makes sense also to use it to describe a culture since leaders’ behavior is probably the biggest driver of culture. It’s also a nifty and concise way to categorize how individuals and teams spend their time.

👩 Head

Emphasizes data, analysis, strategy, and planning to make the right choices, but sometimes at the cost of moving quickly or bringing everyone along.

❤️ Heart

Emphasizes team cohesion, morale, internal values, having a clear mission, and making decisions that consider the team’s views, not just business outcomes. There are clear traps here, too, if taken too far.

✋ Hands

Emphasizes action and shipping. These cultures move rapidly and iteratively. They tend to break things and are biased toward “fire first, aim later.”

The 4 Cultures

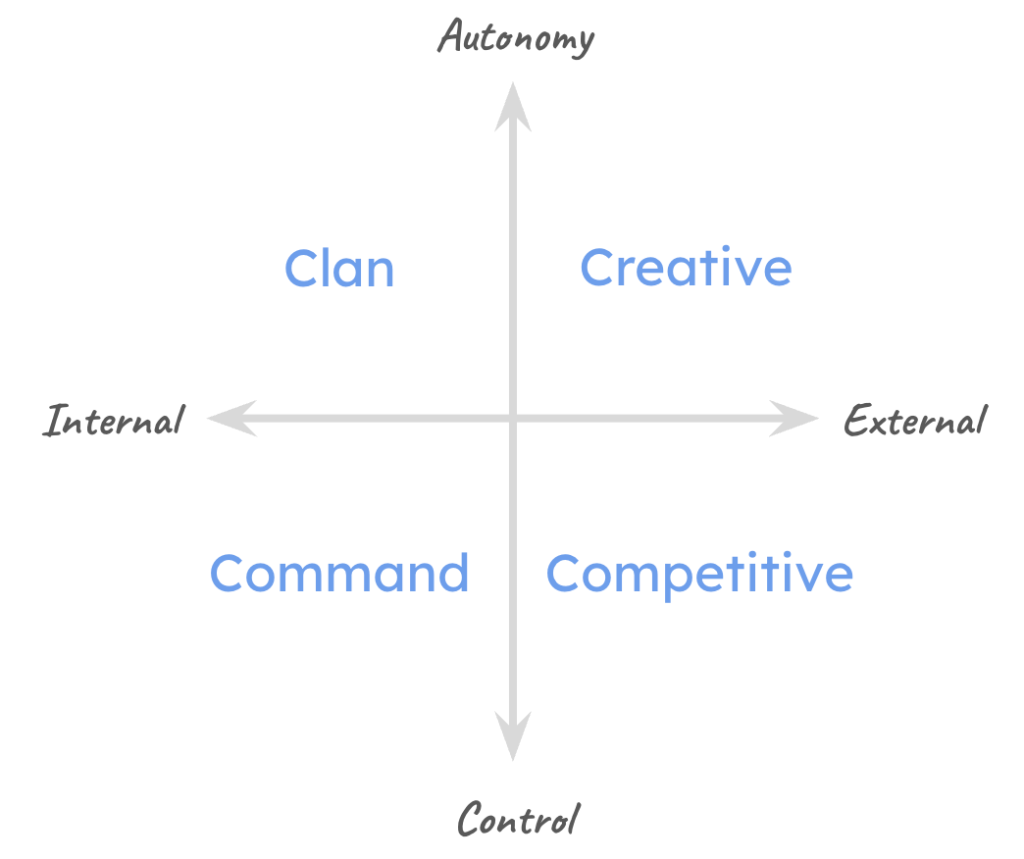

One popular framework, developed by Robert E. Quinn and Kim S. Cameron of the University of Michigan, expresses four competing cultures along two axes.

In each of the quadrants, you have…

Clan culture

Friendly and familial. There is a strong emphasis is on the long-term benefits of developing individuals and teams. As such, mentorship flourishes and there is a strong emphasis on personal relationships, teamwork, participation, consensus and morale. Success is framed around openness to the customer’s needs and care for the team.

Hierarchy culture

Formal, structured, and procedure-driven. Leaders are proud that they are efficiency-oriented coordinators and organizers. Maintaining a smoothly running team is paramount. Long-term concerns focus on stability and results, efficiency, and predictability. Success is framed around reliable delivery, smooth planning, and low costs.

Market culture

Result-oriented, competitive, and goal-focused. Leaders are drivers, producers, and competitors. They are tough and demanding. Their intense focus on winning binds the organization together. Reputation and success are important areas of focus. Success is framed around business metrics — market share, market penetration, etc.

Adhocracy culture

Dynamic, entrepreneurial, creative and risk-taking. Leaders are viewed as innovators. There is a strong commitment to experimentation, discovery, and trendsetting. Long-term concerns are focused on growth and tapping new opportunities. Success is measured by successful new products or services and being a pioneer is important.

I’ve found it handy (and memorable) to use “Clan”, “Command”, “Competitive” and “Creative”.

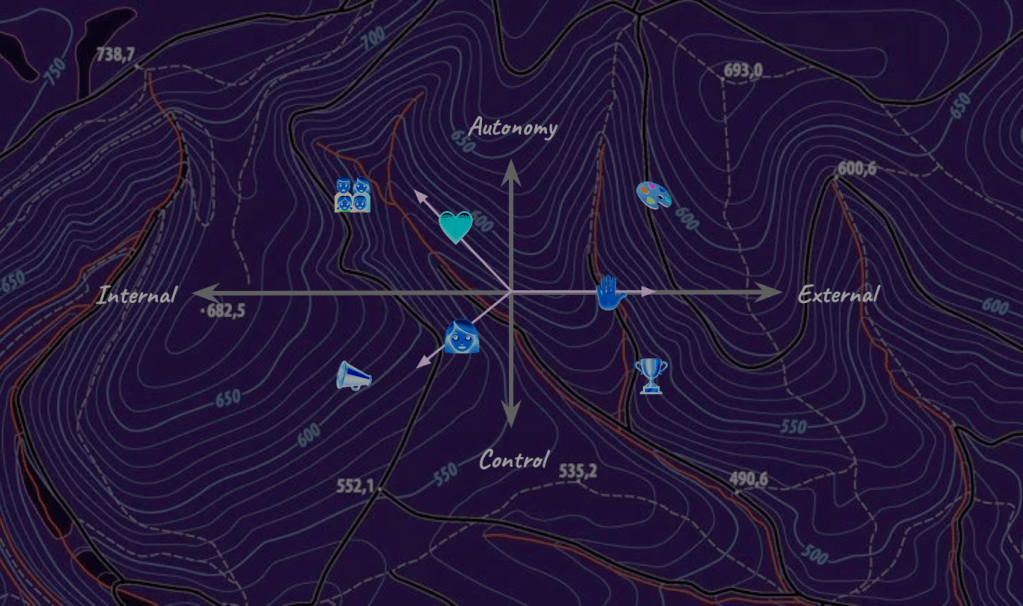

Overlaying these two frameworks looks something like this…

Conservation of Culture

Both frameworks include a concept of “conservation of culture.” Andrew describes Head/Heart/Hands as “a pie chart of these three factors.” Quinn and Cameron describe their framework as the “Competing Values Culture Model.” As much as one may want the best of each, this will be a trade-off since time is inflexible. Where are you spending your time? Planning, analyzing, decision-making, culture building, product building, customer engagement? Where are you asking your teams to spend their time?

Right or Wrong?

These frameworks don’t declare the right cultural biases, just the tradeoffs. It’s up to leaders to determine what tradeoff would be most effective given their industry, product, value to customers, business model, risk tolerance, needed time to market, the nature of the unknowns, and funding.

Here are a couple of quick examples.

- Google’s creativity culture famously encouraged “20% time.” This directly led to Gmail, AdSense, and Google News.

- Amazon’s leadership principles, including “Customer Obsession” and “Bias for Action,” have driven its relentless focus on customer service and rapid innovation.

The trickiest part is that people have strong individual preferences, which is why interviewing for culture is vital before bringing on a new team member. This also applies bidirectionally, though. As you evaluate companies and organizations, determine if leadership clearly understands which tradeoffs are right and if those leaders themselves embody that culture. These frameworks will help you avoid simply asking, “Are they friendly? Will I have autonomy?”

Of course, you need to regularly evaluate your own team against these cultures as well. Has the business environment changed? Has the product matured? Is the risk tolerance different now? Have we learned something fundamental? It can be challenging to be objective since you have your preferred cultural sweet spot. I’ve found it helpful to ponder these frameworks to structure my evaluations.

One stunning example of a cultural pivot occurred at Microsoft. Under Satya Nadella’s leadership, Microsoft shifted from a competitive internal culture to one emphasizing a growth mindset and collaboration, which has been credited with the company’s resurgence

Good or Bad?

A culture that implicitly biases in one of these directions isn’t good or bad. But bad cultures do exist, and these frameworks help describe how that can manifest.

First, cultures go wrong when they become rigid and highly biased in any particular direction. There are common terms for these dysfunctions: “Analysis Paralysis”, “Ready, Fire, Aim”, “Entitled”, “Bro Culture”, and “HiPPO [Highest Paid Person’s Opinion]”. There are other phrases one hears, such as “Meritocracy,” that can be debated, but they will go toxic if there’s no counterbalance. Uber (pre-2017) is often cited as an example. Their aggressive “always be hustlin’” culture under Travis Kalanick led to rapid growth but also numerous troubles, eventually forcing a cultural reset.

Thoughtful companies create a set of well-articulated values that both declare the bias they want and give guidance on when and how to navigate the tradeoffs. Amazon Leadership Principles demonstrate this by asking leaders to balance “Bias for Action”, “Are Right, A Lot”, “Dive Deep” and the rest. Even the most hardcore yet effective cultures (I’m thinking of Extreme Ownership) ensure open space for Heart and Creativity.

Second, cultures go wrong when different subgroups rigidly embody different subcultures without mechanisms to bridge the gap. Most are familiar with the dynamics (or statics?) between platform, infrastructure, product, growth, and sales teams. These teams are set up to have different goals and incentives, which bias their culture. Here, bridging mechanisms are key. That could be a company value like “Disagree and Commit” or processes for prioritization and escalation. Much of leadership training focuses on exercising these.

If one can describe that as “horizontal cultural misalignment,” there’s also dysfunction from “vertical cultural misalignment,” which is often more nefarious and dangerous. Leadership wants “Command and Control,” and the team wants “Creativity and Autonomy.” Or just the opposite — leadership wants creative and autonomous teams, but the teams are asking for direction and guidance (Command). Managing this alignment is honestly one of the best top-level descriptions of leadership. And the mechanism to achieve this is familiar: Setting direction, strategy, processes (and their boundaries), recruiting and talent management, team development, craft development, etc.

But if there isn’t an explicit, transparent, and crisp alignment on the culture leadership is after, despite what the company values say, you are heading for conflict.

We could also explore how different cultures affect diversity and inclusion. We could dive into the complex interactions of culture and remote work. Those topics, and others, are probably already an ongoing conversation within your teams. I hope “Head, Heart, Hands” or “Clan, Command, Competitive, Creativity” can help make those conversations crisp and compelling.

Leave a comment