I am fortunate to have led engineering teams in (and through) various stages — from founding engineer to early startup to late stage and public companies. Reflecting, there were some particularly brilliant technical decisions and some less so. Among them were a set of decisions I found particularly game-changing, not because of the decisions themselves, but simply because a decision was made at all.

These all fall into the category of “Engineering Standards.” I don’t think I’ve encountered a company that hasn’t set these to some extent. Most early-stage engineering teams encounter and make a set of these technical and process choices with little trouble. After all, these are required to build even the first iterations of your product. These include application frameworks, cloud/infrastructure services, CI/CD, coding standards, and testing.

Any software leader can certainly rattle off this list of fundamentals. Setting them well increases current velocity and avoids future friction. However, there are whole other categories of standards that result in an outsized impact on engineering velocity, quality, and craft. That’s because these standards, even though they are not urgent for a new startup, are extremely challenging to implement beyond a certain scale. Yet they are critical for the long-term success of the engineering team.

So, here are my Top 5 Missed Engineering Standards, in order of my personal experience.

1. Customer Analytics Logging

Logging technical functionality, such as service requests, errors, and exceptions, is something few engineering teams ignore. Most application frameworks provide this out-of-the-box. However, the ability to understand and analyze how users interact with your product is also a critical business need. How this is done needs to be determined early, yet it is not often top-of-mind for engineers.Perhaps that is because there are a lot of forward-thinking concerns that need addressing regarding customer privacy, security, and scale. The “customers” of this data are product managers, data scientists, and/or business analysts, requiring cross-discipline coordination. Furthermore, this coordination is more complex than the typical cross-discipline coordination. Here, it’s not a single engineering team working with a single PM on product definition. It’s many engineering teams attempting to serve the future needs of all PMs.

Why can’t this wait?

Without some standard, you will develop disconnected, unreliable, and inscrutable data. Data analysis then requires costly, slow, and unreliable data analysis. The business risks making bad decisions based on messy data. Attempting to implement customer analytics after reaching this point is much harder than if you had started with some standard because…

- Your company wants to fix its data problem but doesn’t want any currently measured KPI to change. This contradiction is particularly problematic if the company previously commented publicly about such KPIs.

- When analytics isn’t part of the initial design, adding it later often requires modifying core application components. You might need to restructure database schemas or frontend architectures to accommodate user event tracking, potentially causing service disruptions or requiring complex migrations.

- Retrofitting analytics often leads to messy implementations. As you attempt to design your analytics standards, they align well with some existing product components but are very misaligned with others. You will always encounter misalignments, even when you set the standard early (e.g. fundamental UX differences between web and mobile). However, these misalignments compound when no standard exists, possibly to the point of infeasibility.

When analytics is considered from the start, it can guide the component design of the system toward a cleaner design.

Where to start

Like with all of these standards, the place to start is to simply declare a standard. Designing the perfect data architecture is probably not the goal (let me know if you’ve ever achieved this), and it will need active management. You will quickly run into tradeoffs entailing the degree of specificity of logged customer events, platform differences, and accuracy:

- Are we just logging every click with the ID of the DOM element, or are we explicitly tagging every click with an explicit customer intent (e.g., “login”, “purchase”, etc.)?

- Are we matching the data schema across web and mobile?

- How are we ensuring accuracy and reliability?

But starting with something gives you a chance. Going too long with nothing could mean the business.

2. Performance and Latency

Quality is a constant consideration of software engineering, and speed and latency are rarely ignored. Nonetheless, tech debt accrues over time, bug backlogs grow, scalability issues emerge, reliability hotspots erupt, and product performance degrades. Once that happens, perhaps bug SLAs are imposed, scalability projects begin, incident response and analysis processes are tightened, and a set of product performance initiatives get kicked off.

Here’s the thing. Fixing the bug backlog, scalability, and reliability issues is often “just work”. It’s hard work, but feasible, and I’m guessing you have personally experienced several successes doing these things.

Why can’t this wait?

Performance is different. Once your product becomes “slow”, it’s too late. In my experience, I think I’ve only ever seen two effective approaches to fixing product performance once it’s broken. First, layering a number of performance enhancers (basically, caching layers), which tend to complexify the system, slowing engineering velocity and causing their tricky reliability problems. Second, a wholesale rebuild — maybe of just that component or the entire website. Either is very painful.

Indeed, any sound engineer considers performance as they implement features or architect whole systems. But it’s not enough to simply consider performance or declare it one of the tradeoffs in your project planning. You need to set a standard.

I came to this realization mid-career when I simultaneously observed teams that did this and teams that did not. Teams that did baked performance assumptions into their design and estimates of engineering effort. There were still tradeoff conversations (for example, with PMs), but there was a standard, and it meant something. Teams that didn’t have a standard would say things that effectively sounded like, “Well, if we wanted it to perform to that level, we never would have built it like this.”

Put another way, attempting to retrofit quality standards such as…

- Bugs must be triaged after H hours and resolved after D days

- The on-call engineer must respond to an after-hours page in M minutes

- The site or service SLA is 5-9s of uptime

…might be met with grumbling, and will take effort, but are imposable.

Retrofitting standards like…

- All web pages have an LCP of 2s at the 90th percentile

- All backend service calls have a response time of 100ms at the 99th percentile

…well, that ship might have already sailed.

Where to start

Quite simply, declare…

- All web pages have an LCP of 2 seconds at the 90th percentile

- All backend service calls have a response time of 100 ms at the 99th percentile

- The mobile app has a 90th percentile cold start time of 3 seconds and a warm start of 1 second

- etc…

You can decide the strictness of these SLAs and what the reactive process is when violated. But simply setting these expectations tells engineers what good is; without them, the other business pressures will win.

3. Automated Testing Strategy

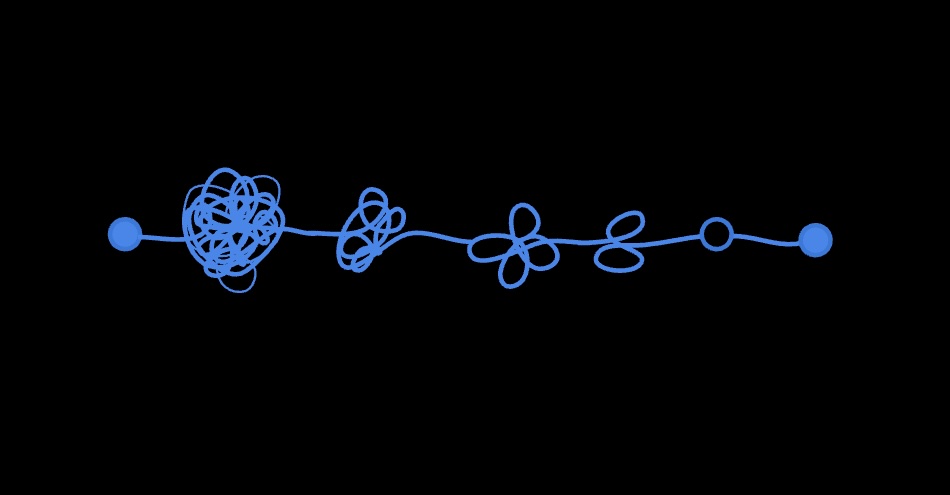

Early on, the team decides on how automated testing is done. Whatever application framework they choose certainly includes mechanisms for unit testing. They decide on the framework for integration and end-to-end testing. Sufficient tests are required and enforced for all code changes. Soon, the build system becomes painfully slow and unreliable as the number of expensive integration and end-to-end tests grows exponentially. Exacerbating the situation is that you need to set up a complete test environment to even run these tests. As the system grows with more and more components and services, the reliability of this environment reaches a tipping point.

The team makes improvements by investing in more hardware for automated testing and begins segmenting and sharding test execution, but this is a losing battle. The number, complexity, and costs of tests continue to grow exponentially. Moreover, compounding the challenge is that engineers never spend nearly the same time refactoring their automated tests as they do their production code. Typically, one writes or updates tests just within the scope of that particular code change. After all, tests are supposed to be light and fast, so holistic maintenance is not top-of-mind… until it suddenly needs to be.

Why can’t this wait?

This is a painful situation because once you reach that tipping point, the effect on the engineering team compounds. Loss aversion means one feels very uncomfortable removing tests, fearing it’ll be the one that prevents a future major business incident. When solid software design is rarely applied to the myriad of automated tests, it can become prohibitively hard to scrutinize the effect of removing, or even refactoring, tests.

Where to start

Like the others, teams often simply rely on handy wavy concepts in the beginning: “Use the testing pyramid” or process guidelines like “All code changes include tests.” I recommend taking this further by simply defining an automated testing strategy. In it, I’d include…

- When and how to use specific types of automated tests, including clear boundaries of overuse and underuse.

- Boundaries on the time, resources, and reliability of automated testing are used within the dev cycle. Decide what happens when they are crossed.

- A clear and maintainable way to assign team attribution (ownership) of every automated test.

4. Tracing

All application frameworks and services include request and error logging out of the box. They include “release” and “debugging” modes that help engineers diagnose problems. These are sufficient when developing an application. On the flip side, at scale, there are several sophisticated (and expensive) monitoring and analysis tools to help you understand your highly distributed system. When your system is basically frontends calling a monolithic app server that makes calls to some persistent storage, deploying one of these tracing tools is overkill.

Soon, new features proliferate. Maybe the business pivots a bit… or a lot. The number of customer-facing surfaces, APIs, controllers, and database tables grows. Some important customer (or the CEO) runs into a product issue, and you comb (grep) through disparate logs spewing from very different parts of the stack to figure out what happened. It’s not difficult to find exceptions, but you can only guess how upstream components react to them or if these are even the exceptions you are looking for.

Why can’t this wait?

Quite simply, waiting until this sort of scenario has already occurred does a big disservice to the customer and business. And the fumbling around to understand and fix quality is not a good look for the engineering team.

Where to start

The more scalable, robust, and expensive tools can be deployed once the business can bear them. Early on, it might be sufficient for that tool to simply be ‘grep’. However, declare and standardize on…

- How a customer/user ID will be plumbed and logged through the stack (with sufficient consideration for privacy and security)

- How a “request ID” will be plumbed

- How a “caller ID” will be plumbed

This need not mean your system requires explicit API keys or service-to-service auth. But lay the groundwork. As with all these standards, doing this early is a strong motivator for engineers to maintain an operationally excellent stack.

5. Design Systems

I’ve come around on this one. Why was I skeptical? There were a couple of reasons.

First, in my experience, the proposal to create and enforce a design system came from Design leadership to ensure design consistency across products, platforms, and customer touch points. “Design consistency” is clearly a good thing, but difficult to quantify and, therefore, challenging to prioritize against other foundational work. Furthermore, those advocating for it would cite the effectiveness they’ve experienced using a robust design system at large, scaled companies, leaving it prone to counterarguments about how our much smaller team could maintain such a thing.

Second, proposals to implement design systems gain mindshare when a company finds traction across multiple platforms, products, and major features. But at that point, retrofitting to a design system feels, and probably is, infeasible. Even if you can find the engineering space-time to replace all of the UI elements, you’re risking significant breaking changes to technical operations (e.g., logging and metrics) and customer engagement.

Why can’t this wait?

This is precisely why setting up a standard design system early is critical. There is a point of no return, technically, as described above, and organizationally. As new engineers and designers join the team without “this is how we do this,” you will continue to dig this hole.

Where to start

At an early stage, you do not need a significant investment. You don’t need a Design Systems Team. You can decide to standardize on a component library framework such as Storybook, Styleguidist, or Docz. Or begin with a pre-built Design System such as Material UI, Chakra U,I or Ant Design.

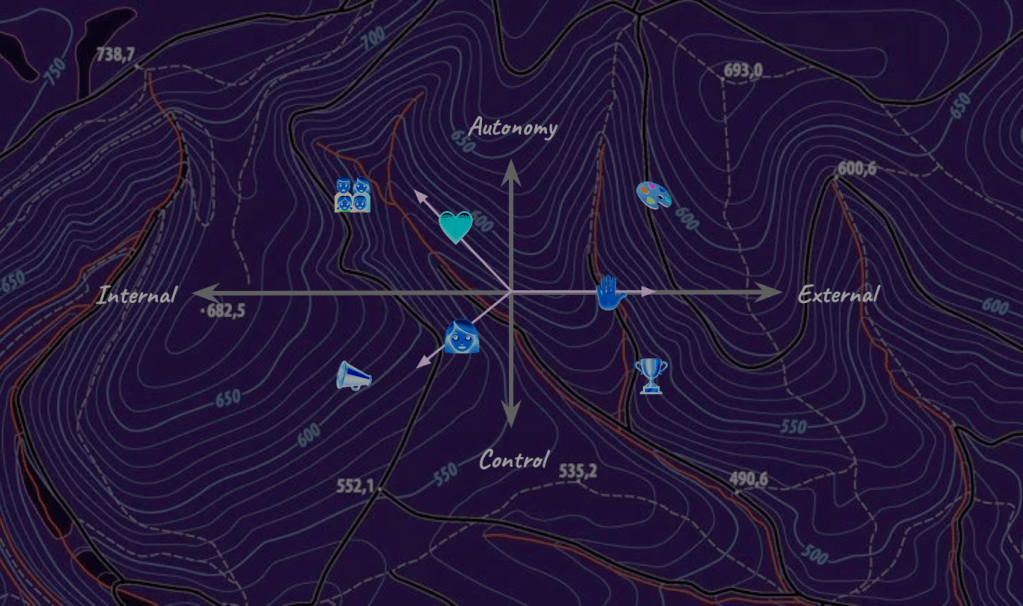

The actual choices for these standards need to be thoughtful and align with the nature of the company’s business and values. Customer analytics logging, performance metrics, automated testing strategy, tracing, and design systems all share a common thread: they’re exponentially more complex to implement retroactively than to establish early.

As you implement these standards, involve your team in the decision-making process. This creates buy-in and ensures the standards reflect the collective wisdom of your organization rather than top-down mandates. Ultimately, engineering standards are about making the implicit explicit. They transform tribal knowledge into shared understanding and convert good intentions into consistent practice. In the chaotic world of software development, they are your technical North Star—guiding decisions when pressure mounts and complexity increases.

What makes these standards particularly powerful is that they create a virtuous cycle. When properly implemented, they don’t just solve the immediate problems they address—they enhance communication, align expectations across disciplines, and create a culture of technical excellence. Engineers make better decisions when operating within clear boundaries that have been thoughtfully established. The goal isn’t to create bureaucratic overhead but to establish technical guardrails that accelerate development rather than constrain it.

What missing engineering standards would you add to this list? I’d love to hear your experiences in the comments below.

Leave a comment